The Caucasus are the mountainous area between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. Now divided between Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and several Russian administrative republics, it was, in its rug producing heyday (the 19th century) a group of Russian Empire provinces. The southern border with Persia was defined as the Araxus River, and the northern reaches extended to the Greater Caucasus mountain range. Except for a few larger towns like Baku, Shemakha, Erivan, Tiflis and Shusha, the population resided in virtually uncountable mountain villages that were comprised of numerous ethnicities and language groups.

In general, Christians were to the west in Armenia and Georgia while those of Islamo-Turkish extraction settled in the east along the western Caspian (from Lesghistan in the north to Shirvan-Baku in the south). In the Moghan steppe to the very southeast were a group of tribes sharing designs and ethnicity with closely related Persian nomads across the border. It must be emphasized that until the border was formalized and closed in the 1860’s, peoples, designs, and rugs moved freely through the area of Northwest Iran and the Caucasus, and the intermingling of influences is evident in the surviving antique Caucasian rugs.

The second half of the 19th century was the most important for Caucasian rugs, and most available antique Caucasian carpets are from that era; although the oldest examples – the Shusha Karabagh “Dragon” carpets – date well into the 17th century.

It should be noted that virtually all Caucasian carpets are in scatter sizes, with prayer (niche) rugs generally smaller. Kazak rugs are often square in format while runners and long carpets are more of an eastern or southeastern specialty. Some large, gallery format carpets were woven in Karabagh, and soumac flatwoven carpets up to 20’ long are known.

Rugs can be roughly divided by weave and thus geography. From the southwest come the coarsest, most strongly abstract pieces, the Kazaks. These have long pile, large areas of plain color, and wholly abstract geometries. There are numerous subtypes assigned to particular village origins. The villages of Bordshaly, Sewan, Karachof, Lori Pambok, Lambalo are all famous in rug lore. But plenty of artistically significant pieces have no exact attributions.

The Karabagh area just to the east of the Kazak region, also wove long pile carpets, but often with a Persian influence. Often lumped with Kazaks, many are attractive representatives of the group.

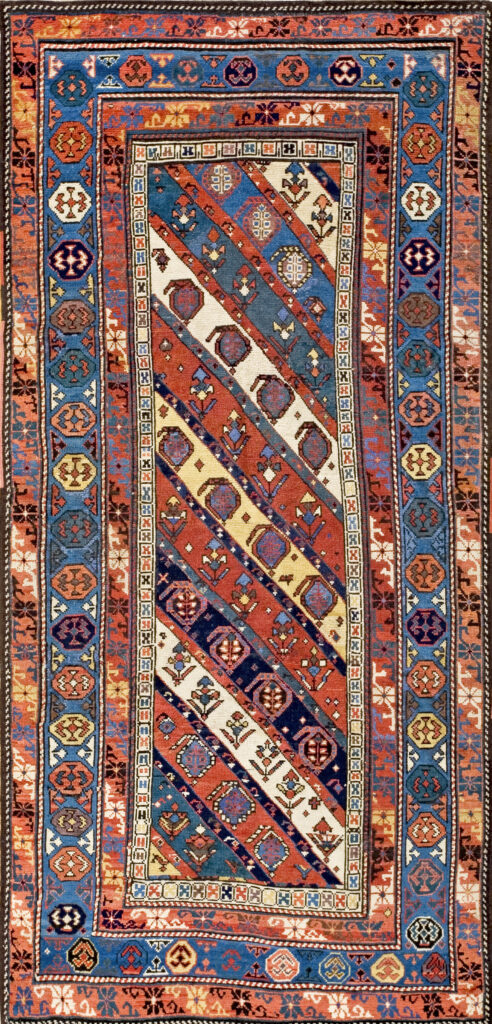

The Gendje district is to the east and is best known for its colouful, diagonally striped long rugs, of which our number 18731 is a classic example.

The short pile eastern Caucasian rugs have wider color palettes and more intricate designs than do the western Caucasian pieces. Kazaks average about 40 knots to the square inch, while Kubas and Shirvans run about 70. The wild power of shaggy Kazaks is transmuted to elegance and precision in Kubas and Shirvans. All Caucasian rugs are symmetrically (Turkish) knotted.

The best known of the fine weave, short pile eastern Caucasian rugs originate in the Kuba (north) and Shirvan (south) areas along the west Caspian. Like the Kazak area, there are numerous village subtypes, each with its characteristic design(s), weaves, and color schemes. Among them is the Karagashli (no. 20807), Marasali (almost always in prayer rug format, no. 18769), Zeychor (21797, 19632), Lesghi (17967) and Chi-Chi (21869)). There are plenty of fine quality pieces, however, that have no precise village attribution (our 6583, 19663, for example), but are still worthy of attention.

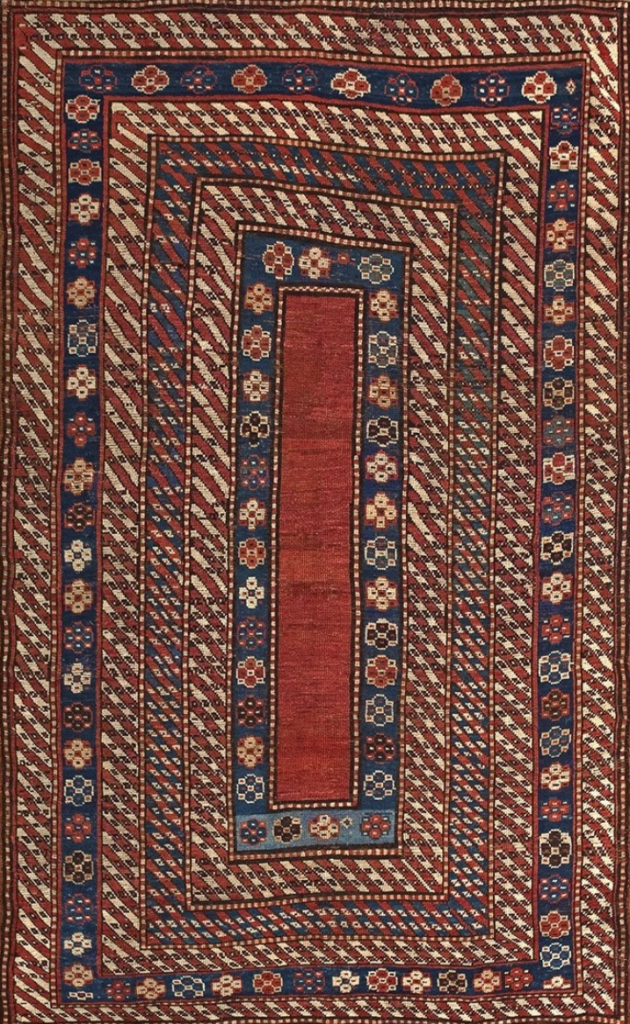

Rugs from the steppe area to the extreme southeast have their own special character. The Talish long rugs often have open, plain fields , while Moghan rugs often have smaller repeating designs.

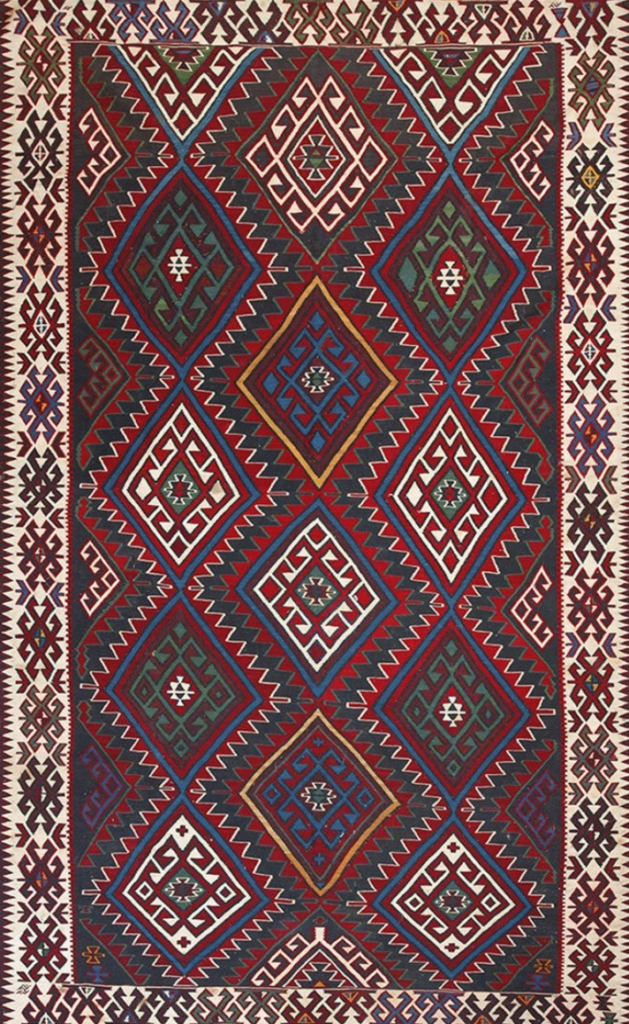

Flatwoven rugs were also made in the Caucasus. The weft-wrapped soumacs, primarily from Kuba, are found in room sizes, usually with colourful repeating medalions. Lighter in weight than soumacs are the banded Shirvan and multi-medallion Kuba kilims, generally in 6’ by 9’ sizes. Of course, the relatively coarse technique precludes fine details, but they are bold and wholly geometric, and work well as wall hangings as well as on the floor.

This is only the briefest overview of a very complex and elaborate rug genre – the subject of numerous books and specialist articles. We will periodically return to this always popular and fascinating area in our blog when something of superior quality and artistic interest catches our attention.

*written by Dr. Peter Saunders

Leave a Reply